- Your cart is empty

- Continue Shopping

Securing Innovation: Effective Patent Management for Life Sciences Entrepreneurs

Securing Innovation: Effective Patent Management for Life Sciences Entrepreneurs

- Atlantis Bioscience

- Blog

- Reading Time: 11 minutes

Table of Contents

Patent protection is a critical form of intellectual property (IP) in the life sciences industry, providing exclusivity to inventors and companies that drive innovation. A patent, granted by the government, gives the patent holder the right to prevent others from making, using, or selling the patented invention without permission. This exclusivity is particularly valuable in fields like biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, and medical devices, where the development of new treatments and technologies often involves high costs, long development timelines, and significant regulatory hurdles.

Value of Patent Protection in Life Sciences

Exclusivity and Incentives for Innovation

A patent grants its holder a 20-year period of exclusivity from the filing date, during which others are prohibited from commercially exploiting the invention.

As the sole manufacturer of a patented drug, they face no competition and can set prices to recover investment costs and based on what insurance companies or patients can afford. In the U.S., drug patents typically expire after 20 years, allowing other companies to produce cheaper, chemically identical generic versions. This competition from generics often leads to significantly lower prices for consumers.

This period of legal monopoly period encourages companies to invest in costly R&D by providing time to recoup expenses and profit before generic competitors can enter the market, which is especially important in industries like pharmaceuticals, where drug development can take a decade or more.

Patents as Key Assets in Early-Stage Life Science Companies

During the early stages of development of emerging life science companies, they may not yet have revenue-generating products, but holding a patent can be a crucial way to demonstrate the novelty and potential impact of their inventions.

Patents as a Business Asset

Patents also serve as powerful tools in negotiations with collaborators, licensing partners, or even competitors, providing leverage in strategic partnerships or joint ventures.

When a patent is granted, the invention becomes the property of the inventor or company, and like any other business asset, it can be bought, sold, licensed, or used as collateral.

Licensing the patent to others, for instance, can generate revenue through royalties while still maintaining ownership, spreading the risk and generating income without direct involvement in production. The licensee takes on the responsibility of bringing the product to market.

This can be an effective way to generate revenue and spread the risk of development, especially for smaller companies or research institutions that may lack the resources to commercialize their inventions independently.

Alternatively, a company might sell the patent outright or use it to negotiate broader collaboration agreements.

Criteria for Patentability

When pursuing patent protection in the life sciences, inventions must meet several key criteria to ensure that they qualify for patentability:

1. Novelty

The invention (as defined in the claims) must be new, i.e. it must not be disclosed in the public domain before the filing date of the patent application. This includes prior publications, conference abstracts, oral or poster presentations, and any non-confidential information shared with potential buyers or the public.

Such prior disclosures are known as “prior art” and can invalidate the novelty of an invention. Therefore, confidentiality is essential until a patent application is filed to safeguard the novelty.

2. Inventive Step

The invention must involve an inventive step, meaning it should not be obvious to someone skilled in the relevant field.

This criterion ensures that the invention represents more than just an incremental improvement or a logical extension of existing knowledge.

Patent Attorneys often engage in discussions with Patent Examiners to determine whether an invention is obvious or not, relying on comparisons with what is already publicly available before the filing date.

To evaluate the novelty and inventive step of a claimed invention, the Patent Examiner conducts a search of public domain information prior to the patent application filing date. This search includes scientific journals, trade publications, and published patent applications from various databases and patent offices, such as the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), European Patent Office (EPO), and Japan Patent Office (JPO). The examiner then creates a Search Report containing the list of documents found.

3. Clarity

The claims defining the invention must be written clearly so that a person skilled in the field can understand exactly what is being protected.

Ambiguity in claims can lead to disputes or difficulties in enforcement, so precision in language is critical.

4. Enablement

The patent application must include sufficient detail for a skilled person to replicate the invention based on the information provided.

This requirement, known as enablement, ensures that the invention can be practically implemented.

For inventions involving a complex chemical compound, the patent application should provide detailed instructions on how to synthesize that compound.

For invention pertains to new therapeutic uses of an existing drug, the patent application needs to provide evidence that the drug is effective for the newly claimed use. For example, if a drug is already known to treat cancer, but the patent seeks protection for its use in treating diabetes, the application must include data or studies showing that the drug can successfully treat diabetes. Similarly, if a drug previously used to manage hypertension is now being claimed for treating neurological disorders, the patent would need to provide clear evidence demonstrating its effectiveness in addressing those specific neurological conditions.

What can be Patented in the Life Sciences Sector?

Medicines Chemical Entities

New medicines, including new uses, biosimilars, and biobetters, can be patented like any other new chemical entity. These new chemical entities are typically claimed by their core structural formula and its variants, such as derivatives and isomers.

Patents can also cover new formulations, therapeutic regimens, and manufacturing processes for these medicines. It is common practice to include claims for treatment methods and production processes related to the new medicament in a single patent application, as long as they are based around the new medicament.

DNA And Proteins

DNA and proteins are considered chemical entities by Patent Offices, including artificial constructs like cDNA and genetically engineered proteins. Patent applications must provide details about DNA, polypeptide, and peptide sequences, as well as the intended use of the new gene or protein. If the invention involves identifying a new gene or polypeptide, claims for vectors or plasmids containing these genes and host cells with such vectors/plasmids can typically be included in the same patent application.

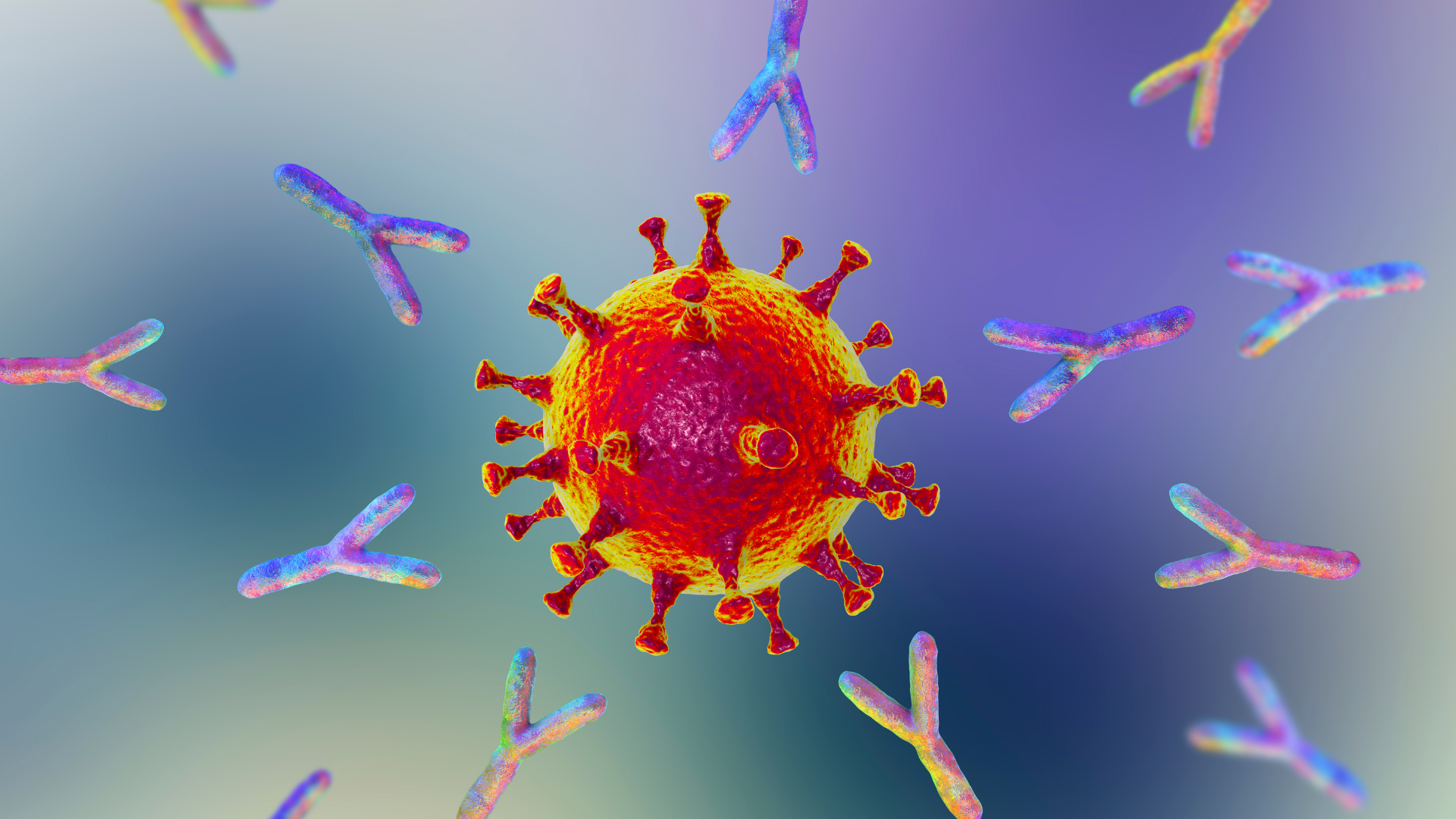

Antibodies

Ways to claim antibodies in patent applications:

1. Antibodies Defined by Epitopes:

Epitopes can be claimed through specific monoclonal antibodies that bind to them or by detailing the continuous or discontinuous amino acid sequences of the epitopes within the antigen. This establishes a clear connection between the antibody and its target.

2. Antibodies Defined by Sequence:

Claims can include specific amino acid or nucleic acid sequences of the Complementarity-Determining Regions (CDRs), which are critical for antigen binding.

Applications may range from functional definitions, focusing on binding affinity, to comprehensive claims detailing entire heavy and light chain sequences.

Patent Offices increasingly require detailed structural information, recognizing that small sequence changes can significantly affect antibody properties.

3. Claiming Antibodies as Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs):

Antibodies can also be claimed as ADCs, which link a therapeutic drug to an antibody for targeted delivery. This strategy provides novelty over non-conjugated antibodies, emphasizing the benefits of targeted therapy and potentially improved efficacy.

Micro-organisms

In patent law, “novel” refers to inventions that have not been made available to the public. For example, the first person to identify a new bacterium from a soil sample may have a potentially patentable invention.

If a microorganism is entirely new (e.g., an unidentified bacterium or fungus), describing its creation in words may not be feasible. In such cases, a sample must be deposited under the Budapest Treaty with an International Depository Authority (IDA), fulfilling the enablement requirement across participating countries.

If a bacterium is claimed in an isolated form, it is considered novel compared to its presence in a previously-known soil mixture. To be patentable, the bacterium must demonstrate a practical application and exhibit sufficient differences from previously known bacteria that serve a similar purpose.

When a new microorganism is derived from a known one (e.g., inserting a plant gene into E. coli), the patent application can describe the method of making it in words, satisfying the enablement requirement. For example, a claim could specify an E. coli mutant that produces ethanol.

Human cells, transgenic animals and plants

Similar principles apply to human cells. For instance, isolating a unique human cell line may qualify for patent protection. The discovery of stem cells has led to numerous patent applications, especially for induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cell lines and methods for differentiating iPS cells into specific cell types.

If the introduction of a foreign gene into a known organism creates a novel and non-obvious transgenic organism, then that organism may be eligible for patent protection.

Medical Devices

Biotech-based medical devices include blood or urine testing devices (like glucose monitors and pregnancy tests), implantable devices (such as taxol-coated stents and synthetic grafts), and injectables (like insulin and epinephrine pens).

In addition to the main device, selling disposable accessories—like cartridges or dip-strips—can create an additional revenue stream, so patent claims should also encompass these accessories. For example, a patent application for a new antibody against a peanut allergen might include claims for the antibody itself, a device that detects the allergen using that antibody, a cartridge for the device, and a method for detecting peanut allergens.

Methods And Processes

Method and process patents typically outline the specific steps for performing tasks or producing products.

Method-of-use patents protect the application of a specific compound for treating a particular disease or condition. They can also cover new uses for an existing drug to treat different conditions. These patents grant exclusive rights to the drug’s use for specified therapeutic purposes.

An example of a method-of-use patent is Botox, originally used for cosmetic wrinkle reduction. It later received a patent for treating chronic migraines, protecting its specific use in preventing migraines and distinguishing it from its cosmetic applications.

Process patents protect the methods used to manufacture a drug, such as synthesizing the active ingredient or preparing the final product. For instance, a process patent for making an antibody-toxin conjugate with specifications regarding the conjugating reagent.

When to File the Patent Application?

Patent applications in the life sciences field, particularly for drug development, are typically filed early to protect the novelty of the invention. However, there are several key considerations:

Early Filing to Preserve Novelty

Patent applications are often filed early in the development process to ensure that the invention remains novel. This is crucial in life sciences, as any public disclosure—such as publishing scientific papers or presenting at conferences—before filing can destroy the novelty of the invention.

Filing During Drug Development

For new drugs, patent applications are commonly filed during the early stages of drug development, often before clinical trials and sometimes even before a lead compound has been fully identified. This protects the discovery as the drug progresses through preclinical studies and into human trials.

Preclinical Data Sufficiency

While filing early is important, Patent Offices still expect some level of supporting data, even if it’s relatively limited at the early stages. For example, in vitro data showing the drug’s effect on a key biochemical pathway or basic in vivo data from animal studies may be sufficient at this point.

Balancing Early Filing with Adequate Data

Filing too early with insufficient data can lead to rejection or limitations, while waiting too long can result in losing the opportunity to claim novelty.

Academic Pressures and Timing

For inventions arising from academic research, the pressure to publish results can also complicate the timing of patent filings. In such cases, careful coordination between filing the patent and publishing scientific findings is crucial to avoid premature disclosure that could invalidate a patent application.

Where to File the Patent Application – A Cost-Benefit Analysis

When filing a patent application, the commercial potential and scope of patent protection may be initially unclear, so it is often beneficial to consider an international filing strategy. The Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) allows for a single international application, which can later be converted into national or regional applications, retaining the original filing date. This approach delays costs and decisions by 18 months, providing flexibility to gather supporting data while allowing for early filing.

Since patents are national rights and no worldwide patent exists, applicants must conduct a cost-benefit analysis to determine where to file. Ultimately, applicants will need to choose specific countries for prosecuting the patent by converting the PCT application into national or regional filings.

The PCT process has two phases: the international phase, where the application is processed by international authorities, and the national phase, where individual national patent offices handle the application.

Costs

- Complexity: Patents are governed by different laws in each country, requiring local patent attorneys and adding to the complexity of managing multiple applications.

- Monetary Costs: Fees include patent office charges, attorney fees, translation costs, and annual maintenance fees. The more patents, the higher the cost.

Benefits

The benefits of patenting in various countries depend on several factors:

• Competitors and Collaborators: Patents give you the right to stop competitors from exploiting your biotech or pharmaceutical inventions. For example, if you’re developing a new cancer drug, it would be critical to file patents in countries where your competitors are conducting R&D or manufacturing similar products, such as in the US or Europe. Additionally, filing in countries where clinical trials are conducted or where your collaborators operate (e.g., China for biologics production or India for generics) ensures protection in key regions.

• Population and Economy: Countries with large healthcare markets like the US, China, Japan, and Europe are vital for life science patents due to their population size and spending power. Countries conducting clinical trials related to your pharmaceutical invention are often early adopters of new therapies, making them key markets for patent protection.

For instance, the US, with its strong pharmaceutical market and regulatory system (FDA), is often the top priority for biotech and pharmaceutical companies seeking patent protection for novel therapies. China’s rapidly expanding healthcare market also makes it attractive for patent filings, especially for biologics and gene therapies.

• Manufacturing and Supply Chain: Companies should file in countries where their drugs, medical devices, or biologics are likely to be manufactured or imported. For example, Singapore’s advanced biopharmaceutical manufacturing capabilities and the Netherlands’ strong logistics infrastructure make them strategic locations for securing patent protection.

• Technology Specialization: Countries that specialize in specific life science technologies are essential for patent filings. For instance, South Korea and Japan have a strong focus on biotechnology and medical devices, while Switzerland and Germany lead in pharmaceutical innovations. Filing in these regions can protect innovations in cutting-edge areas like immunotherapy, gene editing, or precision medicine.

Steps to Filing a PCT Application through Singapore’s IPOS

To apply for a PCT (Patent Cooperation Treaty) application through the Intellectual Property Office of Singapore (IPOS), you can follow these general steps, based on IPOS guidelines:

1. Filing the PCT Application

Submit the application: You can file an international application under PCT with IPOS. The application can be submitted either online via ePCT, the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO)’s online filing system, or through IPOS’s Patents e-Services Portal.

To qualify for filing an international application under the PCT directly with IPOS, you must be a Singapore resident or citizen.

2. Choosing the International Searching Authority (ISA)

IPOS allows you to select the Singapore office or other ISAs such as USPTO, EPO or JPO. The ISA will conduct a search for prior art to assess the novelty of your invention.

3. Receiving the International Search Report (ISR)

The ISA will provide an International Search Report (ISR) and a Written Opinion on the potential patentability of your invention. These documents help guide your decisions about whether to proceed with national phase filings.

4. Publication of PCT Application

At the 18th month, your PCT application will be published by WIPO.

5. Optional International Preliminary Examination (IPE)

You may request an International Preliminary Examination (IPE) by submitting a Demand Form. The examination provides a second assessment of patentability and can help strengthen your application before entering national phases.

6. International Phase

The international phase lasts up to 30 months from the earliest filing date of your initial application, giving you time to evaluate the ISR, assess commercial viability, and decide in which countries to pursue patent protection.

7. Transition to the National Phase

Before the end of the international phase, decide in which countries you want to seek patent protection. File national applications in those countries, and submit the necessary translations and fees.

Conclusion

Having a strong patent portfolio in the life sciences sector has become critical business tool, helping life sciences companies leverage patents for licensing, joint ventures, and strategic partnerships, ultimately spreading development risk and driving innovation forward. The importance of early and well-timed patent filings cannot be overstated, especially given the academic and commercial pressures of the life sciences.

From a global strategy perspective, the PCT provides life sciences companies a vital window to assess the commercial viability of an invention across multiple markets before making costly commitments to national patent applications. Filing strategies that consider key markets not just by size but by potential competition and collaboration opportunities further enable companies to maintain a competitive edge and influence market entry timelines.

References:

- https://www.wipo.int/en/web/patents/

- https://www.wipo.int/pct/en/

- https://www.uspto.gov/patents/basics

- https://www.ipos.gov.sg/about-ip/patents/how-to-register/pct-route

- 2021 Whitepaper by Dehns: Patenting of medical and biotech inventions

CONTACT

QUESTIONS IN YOUR MIND?

Connect With Our Technical Specialist.

KNOW WHAT YOU WANT?

Request For A Quotation.

OTHER BLOGS YOU MIGHT LIKE

HOW CAN WE HELP YOU? Our specialists are to help you find the best product for your application. We will be happy to help you find the right product for the job.

TALK TO A SPECIALIST

Contact our Customer Care, Sales & Scientific Assistance

EMAIL US

Consult and asked questions about our products & services

DOCUMENTATION

Documentation of Technical & Safety Data Sheet, Guides and more...